Fitness Tips

Honest Efforts: Don't Mail In Meaningful Work

By: Jordan Wilcher

We tend to write a lot about strategies, methods, studies and other things that influence training. It is not lost on me that the world at large is a swirling vortex of electronic information, much of it being contradictory. I will save most of my thoughts on that monster of a topic, but it does seem that right now the current is largely influencers pushing agendas as firmly rooted in science and practicality as a mylar balloon found 800 nautical miles from its original birthday party.

Despite all of this, I think everyone can agree that training involves effort. Zoom out and look at what humans are physically capable of and it's really amazing what sustained effort in any direction leads to. Ballet dancers, endurance athletes, baseball players, F1 drivers - just a few of the many testaments to sustained effort over time. While most of us aren’t trying to be the next Ohtani or Verstappen, we can take one lesson with us - consistent effort drives outcomes.

The lowest of the low hanging fruit here is frequency of effort, being that you have to train consistently over time for things to happen. There is no getting around this, do the thing to get the prize. We talk a lot about different mental skills regarding this topic and for the sake of this article we are going to assume you are already training consistently.

In reviewing client data for the year we discuss the near impossibility of knowing what perceived effort for each person means. This largely lies on past experiences for each person. For example, most of us don’t know what a nosebleed inducing squat or exercise induced corneal edema feels like, but for some that isn’t even a 10/10 on their scale. The point in all of this? Effort is relative to current capability and past experience.

This brings us to the low hanging fruit I am getting at with this article, the unsung hero called accessory or assistance work.

While we may not be able to know what someone’s perceived effort may be, we can certainly identify disparities in effort between a main lift and accessory work. In short, we can tell when someone mails this stuff in. It's not surprising. Main lifts (especially ones you like) are like tech stocks, while accessories can seem a bit like government bonds. I implore you to invest in your accessory work and keep the effort honest here. The reason behind this is that in a good program they keep the wheels on and act like good background singers. Tissue tolerance, bone health, joint stability and the ability to resist and create rotational force are just a few of the benefits of the accessory work we program. We can delve into the various facets of the aforementioned benefits another time, for this article the emphasis here is to understand they are designed and implemented in benefit of the global picture of training.

So how do we apply this? I will say first and foremost that efforts being form dependent is critical, as how we move when we are fatigued is highly trainable. You can strain and move a bit slower through a rep while maintaining good form. I think it is beneficial to generate some fatigue and stay very conscious of your movement quality as for our intended purposes, fatigue will show up. Having seat time and knowing fatigue is actually pretty important. This doesn’t mean go and crush yourself, but it does mean that accessory work is a good place to safely push up against some fatigue and intelligently meter your effort and form. This also gives us the space to make accessory work fit our personal goals, meaning we can tailor this to address unilateral imbalances, strength, hypertrophy etc. The way I like to challenge this is for people to take a weight they typically use for a given exercise (we see over time people often use the same weights for a given accessory movement). Take a set to form failure and count the reps. If the programming calls for 6-8 reps and you don’t blow up until 30, chances are you need to increase the weight so that you are leaving anywhere from 2-5 reps in the tank or change your rep or loading scheme if your weight access is limited.

Much of this discussion has focused on strength-based metrics because they are easily quantified. However, the sentiment applies to the rest of the supporting movements in a workout.

Don’t mail in your mobility, plyometrics, jumps or throws. Over the course of a year’s time, these efforts add up in a very tangible way. Keep your throws powerful, jumps snappy, and lifts honest.

It all adds up in the end.

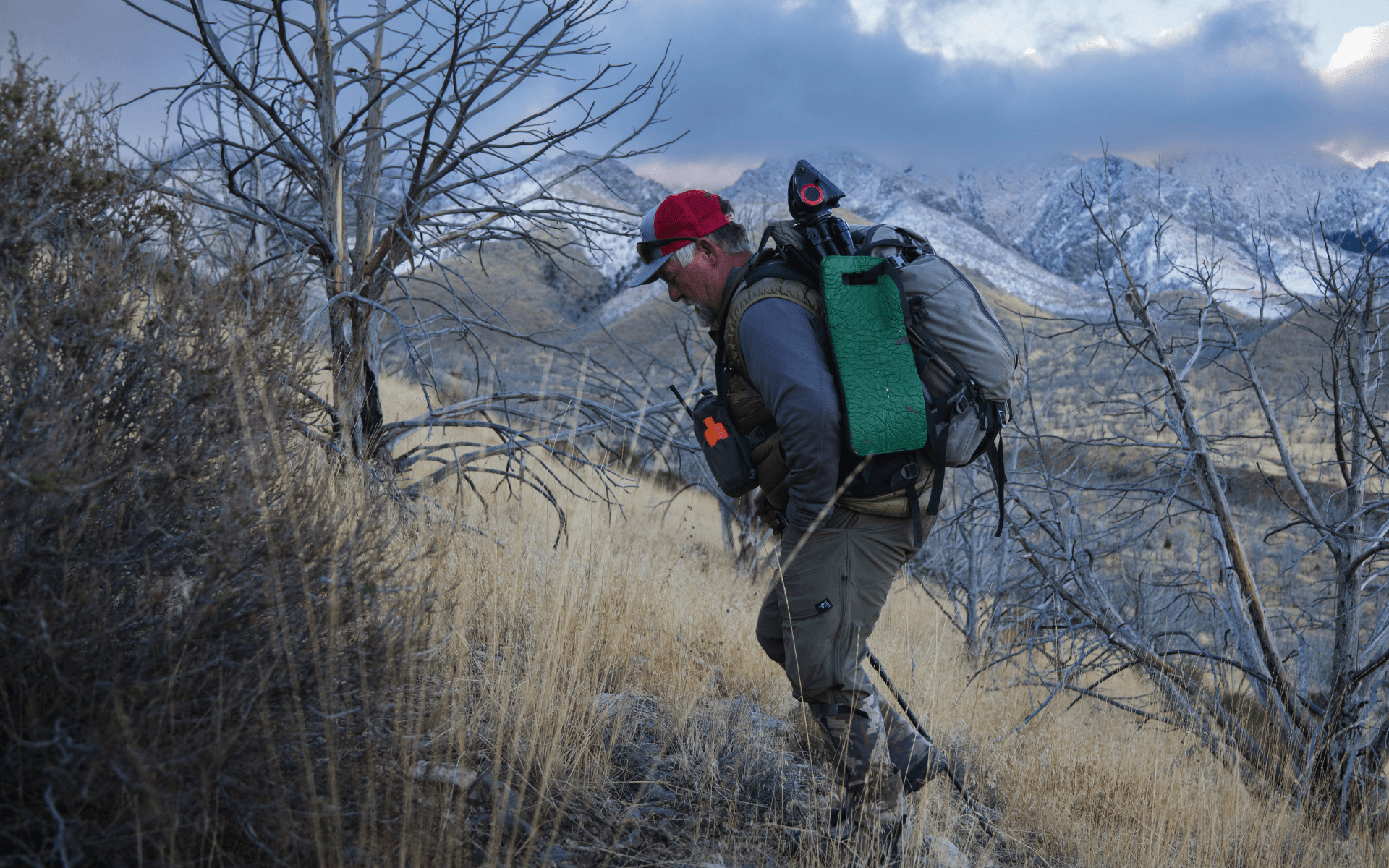

Jordan was born and resides in Nevada. He is an assistant coach at HPPM in addition to working as an RN. Jordan has a curiosity which leads him to a constant pursuit of knowledge in his interests. He enjoys adventures with his family and anything that involves bird dogs or fly rods.

Recent posts

Related Articles

Testing and Assessments

Feb 18, 2026

Do You Know How Much Weight You Should Carry? Determining Your Safe Pack Weight in 10 Minutes

Picture this: You’ve just finished skinning and quartering a bull elk you’ve worked just about every part of your ass off to kill. Now, you have some roller coaster miles ahead of you. The first stretch of that roller coaster is a steep uphill stretch. Then you have yourself a spicy descent before you hit another long uphill, march. You grab your pack and have a look at the meat as it hangs in game bags; you want to get it all back to the truck as quickly and in as few trips as possible. But there’s a problem — you don’t know how much you should load into your pack at one time.

Testing and Assessments

Feb 18, 2026

Do You Know How Much Weight You Should Carry? Determining Your Safe Pack Weight in 10 Minutes

Picture this: You’ve just finished skinning and quartering a bull elk you’ve worked just about every part of your ass off to kill. Now, you have some roller coaster miles ahead of you. The first stretch of that roller coaster is a steep uphill stretch. Then you have yourself a spicy descent before you hit another long uphill, march. You grab your pack and have a look at the meat as it hangs in game bags; you want to get it all back to the truck as quickly and in as few trips as possible. But there’s a problem — you don’t know how much you should load into your pack at one time.

Testing and Assessments

Feb 18, 2026

Do You Know How Much Weight You Should Carry? Determining Your Safe Pack Weight in 10 Minutes

Picture this: You’ve just finished skinning and quartering a bull elk you’ve worked just about every part of your ass off to kill. Now, you have some roller coaster miles ahead of you. The first stretch of that roller coaster is a steep uphill stretch. Then you have yourself a spicy descent before you hit another long uphill, march. You grab your pack and have a look at the meat as it hangs in game bags; you want to get it all back to the truck as quickly and in as few trips as possible. But there’s a problem — you don’t know how much you should load into your pack at one time.

Testing and Assessments

Feb 10, 2026

How Hunters Should Test Their Mobility

The following is an excerpt from the upcoming The Hunter's Guide to Uphill and Downhill Training. I'll be releasing more excerpts in the coming weeks and opening up registration for a pre-sale list with sweet bonuses. Mobility, a.k.a. movement capacity, is misunderstood and under trained in the hunting fitness world. Good movement begins with understanding your current mobility needs. You have to test to get a handle on your current needs. Otherwise, you're firing blanks into the dark. Here's a rundown to how we approach movement testing straight from the book.

Testing and Assessments

Feb 10, 2026

How Hunters Should Test Their Mobility

The following is an excerpt from the upcoming The Hunter's Guide to Uphill and Downhill Training. I'll be releasing more excerpts in the coming weeks and opening up registration for a pre-sale list with sweet bonuses. Mobility, a.k.a. movement capacity, is misunderstood and under trained in the hunting fitness world. Good movement begins with understanding your current mobility needs. You have to test to get a handle on your current needs. Otherwise, you're firing blanks into the dark. Here's a rundown to how we approach movement testing straight from the book.

Testing and Assessments

Feb 10, 2026

How Hunters Should Test Their Mobility

The following is an excerpt from the upcoming The Hunter's Guide to Uphill and Downhill Training. I'll be releasing more excerpts in the coming weeks and opening up registration for a pre-sale list with sweet bonuses. Mobility, a.k.a. movement capacity, is misunderstood and under trained in the hunting fitness world. Good movement begins with understanding your current mobility needs. You have to test to get a handle on your current needs. Otherwise, you're firing blanks into the dark. Here's a rundown to how we approach movement testing straight from the book.

Fitness Tips

Feb 8, 2026

How to Train for Performance Now so You can Walk Mountains When You’re 85

There’s a lot of biohacking nonsense floating around about training for longevity. The truth is simpler. Intelligently designed fitness training is longevity training. You don’t need to sun your butthole or face east while screaming into the wind, or whatever silly shit influencers would have you do. What you truly need to do is consistently train and eat in a way that’s sustainable while moving your fitness forward. It is simple, but it’s not always easy. And it begins with getting your head on straight.

Fitness Tips

Feb 8, 2026

How to Train for Performance Now so You can Walk Mountains When You’re 85

There’s a lot of biohacking nonsense floating around about training for longevity. The truth is simpler. Intelligently designed fitness training is longevity training. You don’t need to sun your butthole or face east while screaming into the wind, or whatever silly shit influencers would have you do. What you truly need to do is consistently train and eat in a way that’s sustainable while moving your fitness forward. It is simple, but it’s not always easy. And it begins with getting your head on straight.

Fitness Tips

Feb 8, 2026

How to Train for Performance Now so You can Walk Mountains When You’re 85

There’s a lot of biohacking nonsense floating around about training for longevity. The truth is simpler. Intelligently designed fitness training is longevity training. You don’t need to sun your butthole or face east while screaming into the wind, or whatever silly shit influencers would have you do. What you truly need to do is consistently train and eat in a way that’s sustainable while moving your fitness forward. It is simple, but it’s not always easy. And it begins with getting your head on straight.

Testing and Assessments

Feb 18, 2026

Do You Know How Much Weight You Should Carry? Determining Your Safe Pack Weight in 10 Minutes

Picture this: You’ve just finished skinning and quartering a bull elk you’ve worked just about every part of your ass off to kill. Now, you have some roller coaster miles ahead of you. The first stretch of that roller coaster is a steep uphill stretch. Then you have yourself a spicy descent before you hit another long uphill, march. You grab your pack and have a look at the meat as it hangs in game bags; you want to get it all back to the truck as quickly and in as few trips as possible. But there’s a problem — you don’t know how much you should load into your pack at one time.

Testing and Assessments

Feb 10, 2026

How Hunters Should Test Their Mobility

The following is an excerpt from the upcoming The Hunter's Guide to Uphill and Downhill Training. I'll be releasing more excerpts in the coming weeks and opening up registration for a pre-sale list with sweet bonuses. Mobility, a.k.a. movement capacity, is misunderstood and under trained in the hunting fitness world. Good movement begins with understanding your current mobility needs. You have to test to get a handle on your current needs. Otherwise, you're firing blanks into the dark. Here's a rundown to how we approach movement testing straight from the book.