Fitness Tips

Can You Stay Physically Ready to Hunt All The Time?

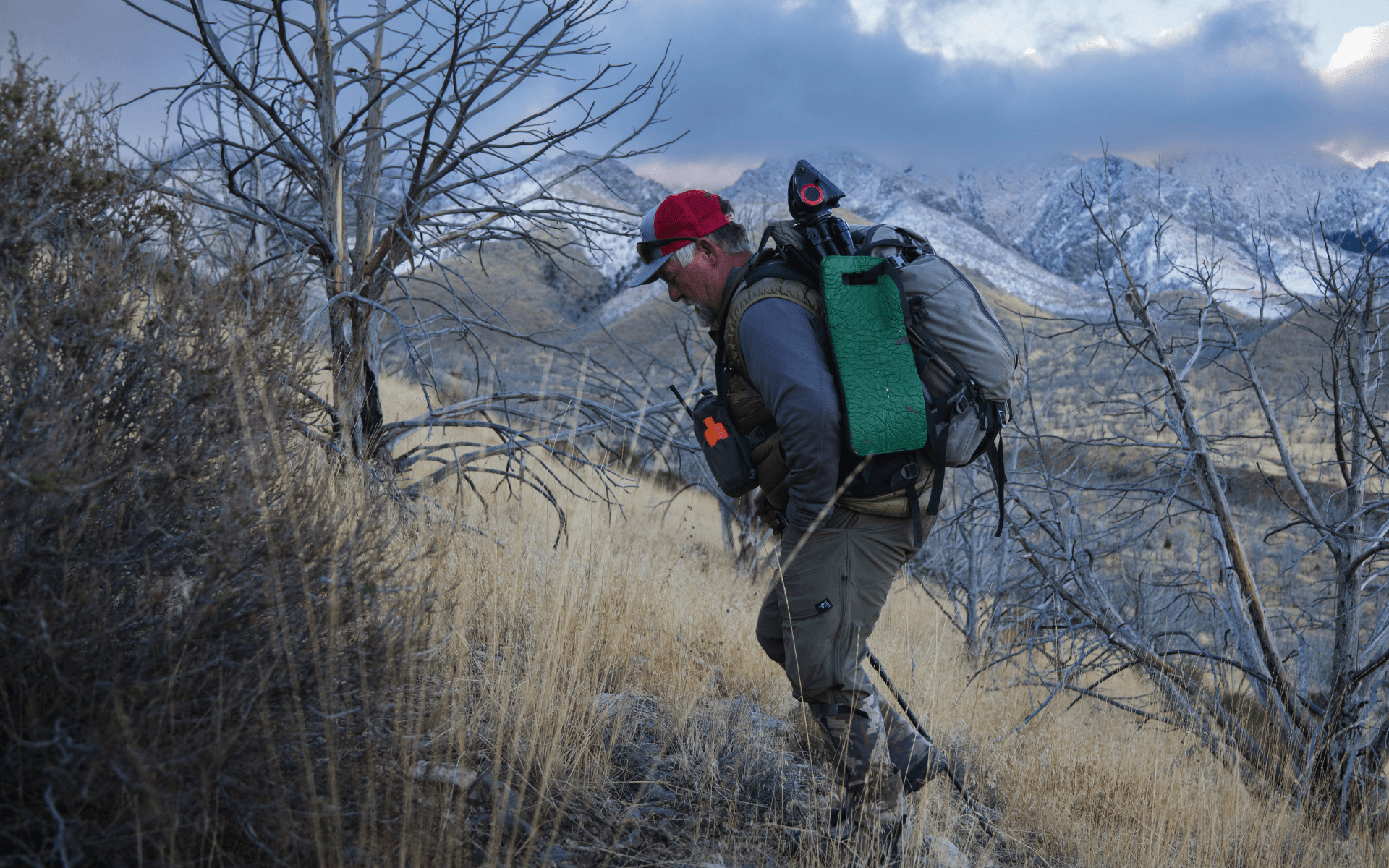

There’s a lot of talk about always being physically ready — especially to hunt. But is that a genuine concept, or is it just a marketing ploy? Could you sincerely hop in the truck tomorrow to go on a big hunt and not get your ass handed to you in a tightly wrapped package of pain?

I have a detailed answer for you — and one I think you’ll like. On the way to delivering it to you, you’ll discover some important truths about how the body works and how it adapts to training. We’ll also cover some training definitions and facts that will prevent you from being baffled by bullshit, while also giving you a deeper understanding of physical training for hunting.

We’ll start the party by giving you the low-down on two often misunderstood training terms.

The Difference Between Fitness and Readiness

Fitness and readiness are often confused and talked about as if they are interchangeable terms. They are not. Fitness and readiness are different things. Here are clear definitions.

Fitness: The combination of physical attributes necessary to successfully complete a task or series of tasks.

Readiness: State of recovery that determines how well you can access your fitness and/or build on it.

Fitness is specific. For example, you can be fit to run the 100-meter dash, or you can be fit to climb Mt. Everest. (Obviously, there are a million other things in between.) Each has vastly different needs, so each takes broadly different types of training. But most people don’t think of fitness that way.

They think of fitness as the way someone looks, or when they see someone with a broad base of physical abilities, but aren’t particularly exceptional in one area. Special operators are a great example (we’ll talk more about them in a bit). As hunters, we mostly want to fall into that second category — we want a broad base of physical abilities built upon aerobic capacity and relative strength. This is based on General Physical Preparedness and General Work Capacity (also more on this later).

Readiness is essentially your ability to adapt to exercise and perform. It is access to your physical resources. When you’re recovered, you have high readiness. When you’re under-recovered, you have low readiness. Here’s an example.

Let’s say your planned workout for today is a solid conditioning effort at the top end of Zone 3 — so, fun hard, not brutal hard. While it may not seem like it, training at that intensity has a relatively high cost. Now, you could go out and do the workout regardless of your readiness. However, if you have high readiness, not only will you get more out of the workout because you’ll have an easier time sustaining the intensity. But you’ll also recover better from the workout because you’ll have more resources available to do it. If your readiness is low, the cost goes up, and it depletes more resources, leaving you with less to use for recovery — putting you even further behind the recovery curve.

It might surprise you, but this is why extremely conditioned people have to be even more mindful of training intensity. They are more efficient, so it’s easier for them to extract resources during a workout. They can dig a deeper hole and tank their readiness in a hurry.

But it’s also true of people without a solid conditioning base. Their thresholds are so low that it’s easy for them to train beyond their capacity to recover, because they don’t have the systems built to recover.

It’s a fine line to walk for all of us.

Now that you understand the difference between fitness and readiness, we’ll talk about how to build fitness that supports readiness. And we’ll begin by talking about what absolutely not to do.

Training That Kills Your Readiness, But Gives You Nothing in Return

Think of training and readiness like a bank account. If you’re consistently taking out big draws on your account, but you don’t have sufficient income to replace the draws, you’ll soon run out of money. Readiness works the same way. If you’re training hard (hard being relative to the person) and not giving yourself the necessary recovery, you will take your readiness bank account into the negative. Not only will you stop making progress, but you’ll also start going backwards.

So, what kind of training makes big draws on your account without any deposits? Constant barrages of high-intensity. This is true for everyone — the ultra-conditioned, the poorly conditioned, and everyone in between. And it happens even if you’re fueling properly and doing the little things to promote recovery. There is just no way to keep up with the draws on your account.

You can’t train “hard” every day and build sustainable fitness or readiness. From a fitness standpoint, high-intensity conditioning must be earned by doing enough low-intensity work to support it. Otherwise, you don’t build the delivery system to support the high-intensity work or to recover from it.

From a readiness perspective, you just can’t bounce back fast enough if every workout is high-intensity because you don’t have enough resources left for recovery. You also train your body to preferentially burn carbs most of the time — even at lower heart rates. This puts a way higher tax on your system, stresses your muscles harder, and tanks your central nervous system. Then the cycle reinforces itself until you feel like Jake Paul after Anthony Joshua landed that cross.

You won’t be fit. You won’t be ready.

Let’s talk about building fitness that supports your readiness.

How to Build Fitness that Supports Your Readiness

We’ll start with two terms I threw at you earlier in the article — General Physical Preparedness and General Work Capacity. How’s about a couple of definitions?

General Physical Preparedness (GPP): A broad foundation of physical abilities such as mobility, stability and structural integrity, strength, aerobic capacity, and movement skills that allows a person to take on a large range of physical tasks with resilience.

General Work Capacity (GWC): The ability to perform work across time at varying intensities without fatigue. (Think of it as GPP + output.)

GPP and GWC are non-negotiables for hunters. First, because doing rugged shit requires a lot of resilience, which in turn requires a handful of fitness abilities. Second, because GPP and GWC are foundational for building the specific prep necessary for hiking heavy uphill and downhill. Third, because each requires the type of training that supports recovery and readiness.

GPP + GWC = Better Recovery

Low-intensity aerobic training is crucial to GPP and GWC because it’s necessary for building endurance. But that’s not all, folks! It’s also necessary for building your recovery systems. Zone 1 and 2 training builds the “highway” that carries oxygen and nutrients to your muscles. This is, of course, important during exercise. But it’s just as important for recovering from exercise. Without building the highway, you can’t effectively and efficiently get muscles what they need to recover. There’s another thing it does for you.

Zone 1 and 2 training installs your nervous system’s “recovery switch.”

I’d be real dang surprised if you’ve made it to 2026 without ever hearing about fight or flight mode (sympathetic drive). It’s your nervous system’s response to threat. To recover well, you have to be able to turn it off. Whereas constant high-intensity training flips the fight or flight switch and tends to leave it on, the right balance of low-intensity training turns it off. Not only that, it helps you live more in rest and recovery mode (parasympathetic drive) while raising your threshold for entering fight or flight mode. Here’s some nerd stuff about how that works.

Your heart has a direct connection to your vagus nerve, the main component of your autonomic nervous system, which branches into the sympathetic and parasympathetic parts mentioned earlier. Low-intensity aerobic training increases vagal tone by strengthening the connection between the heart and the vagus nerve. As the connection strengthens, it’s easier to lean towards parasympathetic, even while training, and you can switch from sympathetic drive to parasympathetic drive more quickly after intense training. Oversimplified but accurate — it teaches your body to conserve energy and resources during training while also helping your body to redirect those resources into recovery after training. This is one of the main reasons why it’s so important to get a good body of low-intensity work under your boots before adding in higher-intensity work.

GPP’s and GWC’s low-intensity aerobic training is crucial to building fitness that supports your readiness. It trains you to not extract as much from your body during exercise while also helping you “flip the switch” to recovery mode and bounce back faster. This means you can handle more training and more hunting.

GPP + GWC Makes Movement Cost Less

Strength, mobility, and stability are also huge components of GPP and GWC. When you’re strong relative to your body weight, each step you take and each move you make requires less energy. You move more efficiently when you’re mobile and stable. This also reduces energy cost. As it goes with low-intensity aerobic work, when you make movement cost less, you leave more in the tank for recovery. When you extract less, your readiness stays higher. When your readiness stays higher, you’re able to train more frequently and more productively.

It Works Because It’s Layered

The combination of GPP and GWC is such a strong foundation for hunting fitness because it’s constructed in layers. That means each physical ability is developed in the right sequence and given the right amount of work. We already chatted about one example — needing a sufficient amount of low-intensity aerobic work before piling on higher intensity conditioning. The layers work because each training adaptation requires different amounts of time, training frequency, and training volume. If you train too specifically, or with too much intensity, all the time, it’s impossible to drop each layer in the proper place. We’ll provide more detail in list form.

Aerobic capacity (low-intensity) requires at least 8 - 16 weeks of proper training volume and frequency to create lasting change — then it must be maintained.

Once you have a sufficient aerobic base, you can layer on aerobic power (high-intensity) conditioning more productively because you’ve built the highway to make training and recovery more effective.

It takes 8 to 16 weeks to meaningfully and sustainably improve relative strength.

Once you have sufficient relative strength, you can layer on strength endurance so you have more access to that strength over time.

Muscular endurance training is more effective once you’re strong and have a solid aerobic base.

Mobility, movement capacity, and stability training require year-round effort.

Once you’ve laid the general layers, you put specific training on top of them.

You Down with SPP? (Yeah, You Know Me!)

SPP stands for Specific Physical Preparedness. Which is:

The targeted development of physical capabilities to complete a known task or series of tasks.

For a sprinter, that’s direct sprint training.

For an uphill athlete, that’s direct uphill training.

Some events require more specific training than others. However, overly specific training is a detriment to other endeavors. Let’s look at some examples.

We’ll start by sticking with sprinters. They need a lot of specific training because there are very few unknowns in their event. They know how far they’ll run. They know what surface they’ll run on. They essentially know when the event starts and when the event ends (yes, I know they’re trying to run faster each time, but the variance is small). There is also a narrow set of skills necessary to do their sport well. Extremely specific training is necessary for them.

Special operators, on the other hand, need a broad base of physical abilities. Yes, at times they’ll train for specific missions and need more targeted training to prepare for that mission. But even on specific missions, they face a large number of physical unknowns. On top of that, they need a broad base of physical abilities to perform well, even during specific missions. They might have to run, carry, crawl, move under load, change levels quickly, and exfil for an unknown distance. They can’t hyper-focus on one physical ability at the expense of all others.

As hunters, we lean more toward special operators than we do sprinters. While we know that we’ll have to hike uphill and downhill under load, and will need specific preparation for each, there are a lot of unknowns and variables to prepare for. There’s variance in terrain. We may plan to only hike three miles in, then find that the critters we’re chasing are farther in. We may have to run, carry, crawl, move under load, change levels quickly, and pack out for an unknown distance. We absolutely need specific, well-designed, uphill and downhill training — especially under load. But we can’t hyper-focus on it. And we can’t expect to get the most out of it without first laying the GPP and GWC foundation.

We need specific training. But we must progress to it in an intelligent way, and then also perform it in an intelligent way.

This all leads us to answer the big question that started this party.

Can You Stay Physically Ready to Hunt All the Time?

If your training is smart, layered, and consistent, you can stay most of the way ready for most hunts most of the time.

This requires you to:

Maintain solid levels of relative strength and strength endurance

Maintain a solid base of aerobic capacity and aerobic power

Move well

Stay efficient under load

Maintain enough uphill and downhill muscular endurance to not shellac your legs

If you follow a training program (ahem, Packmule) that gives you enough GPP and GWC year-round, you should feel confident heading out on most hunts, even without a ton of specific training. However, to be as prepared as possible, you should have 8 - 16 weeks of specific uphill and downhill training leading up to most Western hunts in the U.S. and Canada.

Now, that said, there are hunts that will require more. For example, in 2028, I’ll accompany a client on a blue sheep hunt in Nepal. It’s a true expedition hunt, with a handful of days hiking into the Himalayas before we even reach sheep country. A hunt like this requires a longer specific runway for full preparation.

All things considered, if you train smart, you should be able to say yes to most hunts without too much physical cost. You won’t be as prepared as you could be, but you’ll still be fit enough to hunt without absolutely crushing yourself.

So, the answer is (mostly) yes. You can stay physically ready to hunt at all times, provided that you build and maintain the right foundation, and with the understanding that a runway of specific preparation is necessary to be as prepared as possible.

—-

Want to know where your hunting fitness currently stands?

Download a free copy of The Hunter's Field test and put yourself through the assessments.

Click >>> The Hunter's Field Test

Recent posts

Related Articles

Testing and Assessments

Feb 18, 2026

Do You Know How Much Weight You Should Carry? Determining Your Safe Pack Weight in 10 Minutes

Picture this: You’ve just finished skinning and quartering a bull elk you’ve worked just about every part of your ass off to kill. Now, you have some roller coaster miles ahead of you. The first stretch of that roller coaster is a steep uphill stretch. Then you have yourself a spicy descent before you hit another long uphill, march. You grab your pack and have a look at the meat as it hangs in game bags; you want to get it all back to the truck as quickly and in as few trips as possible. But there’s a problem — you don’t know how much you should load into your pack at one time.

Testing and Assessments

Feb 18, 2026

Do You Know How Much Weight You Should Carry? Determining Your Safe Pack Weight in 10 Minutes

Picture this: You’ve just finished skinning and quartering a bull elk you’ve worked just about every part of your ass off to kill. Now, you have some roller coaster miles ahead of you. The first stretch of that roller coaster is a steep uphill stretch. Then you have yourself a spicy descent before you hit another long uphill, march. You grab your pack and have a look at the meat as it hangs in game bags; you want to get it all back to the truck as quickly and in as few trips as possible. But there’s a problem — you don’t know how much you should load into your pack at one time.

Testing and Assessments

Feb 18, 2026

Do You Know How Much Weight You Should Carry? Determining Your Safe Pack Weight in 10 Minutes

Picture this: You’ve just finished skinning and quartering a bull elk you’ve worked just about every part of your ass off to kill. Now, you have some roller coaster miles ahead of you. The first stretch of that roller coaster is a steep uphill stretch. Then you have yourself a spicy descent before you hit another long uphill, march. You grab your pack and have a look at the meat as it hangs in game bags; you want to get it all back to the truck as quickly and in as few trips as possible. But there’s a problem — you don’t know how much you should load into your pack at one time.